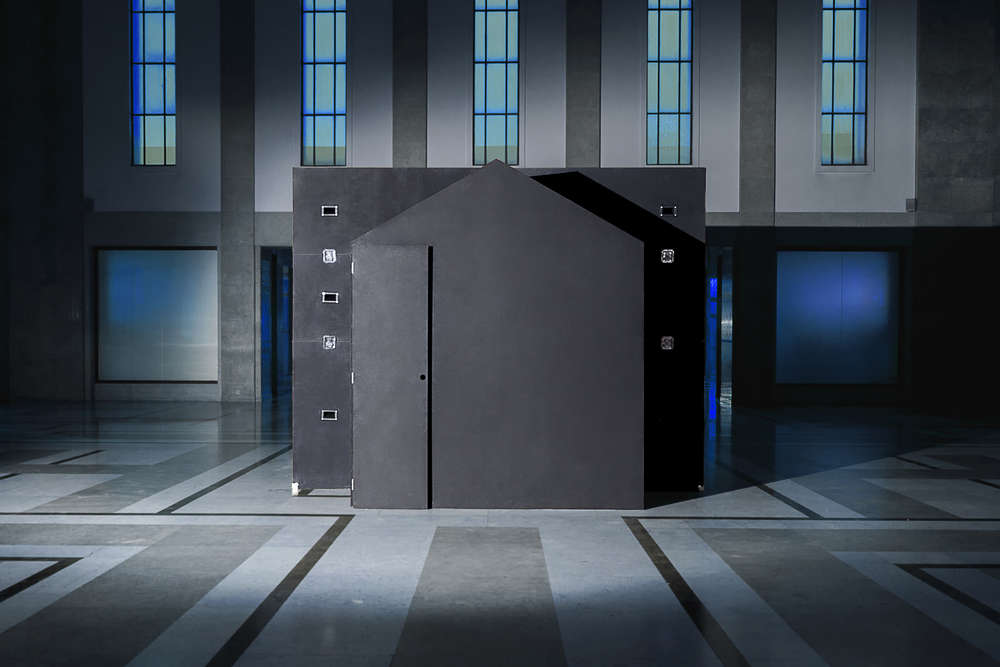

THE CLUB is an installation by BUREAU for the Lisbon Triennale 2016. Conceived as an architecture dedicated to sound experience, it is a noise cabin hosting people for a dense dancing event. This travelling sound system, in the Jamaican tradition, adapts to a diversity of situations and generates, through its architectural presence, a particular relation to the context where it stands.

It is composed of loudspeakers, a DJ booth, a bar and an entrance. In its smaller configuration, it creates a perfect micro dancefloor for about 25 people, entirely enclosed buy the sound architecture.

THE CLUB has produced 5 events for the Lisbon Triennale in different venues. The choice of the hosting spaces has been an important part of the project. Reflecting on the history of Techno music, some forgotten spaces of the city left without purpose have been brought back to life for a night, the time of a party. Palácio Pombal, Mãe d’Água, the ancient prison of Trafaria, the old Maritime Station and finally the Palácio Sinel de Cordes have been transformed, for a night, into unique party venues.

THE CLUB is thus a house. Its shape is casted in the solid block of technical equipment. The sound system is the formwork of this volume, sort of micro-monument, almost classical in its dark presence. The modularity of the components allows for the installation to modify its form in order to adapt to the space that it occupies. The sculptural form of the components has established specific dialogue with each one of the five architectural contexts invested by the club.

DANCING IN THE RUINS

text by Marie Avril Berthet

Architects have quite largely explored the design of nightclubs, theoretically and in their practice. Their explorations formally tend to focus on architectural space and form with little or no consideration for the variety and typologies of musical cultures that nightclubs accommodate. Disregarding historical or chronological patterns, the proposal for THE CLUB aims to investigate if one genre of electronic body music, namely techno music, has the potential to initiate a thread of architectural thinking about clubs.

Nothing is more debatable than a musical genre. Importantly though, people produce spaces to practice and consume forms of arts and culture; and these spaces vary greatly depending on the type of practices they are meant to accommodate. To this extent then, it seems interesting to explore how one architectural design of clubs. Techno in particular did come across as an interesting case study because it strongly resonates with urban politics. Techno is “architecturally informative” in the sense that it’s a musical trend that emerged in and developed in an urban context of major socio-economic changes. In this sense, techno music has as much to say about the production of architectural spaces as it does about the relation between architecture and cities.

Techno is the music of late capitalism. If any consensus is to be found around its definition, it is that it frew in the mid-80’s, out of the ruins of the city of Detroit. Detroit’s wreckages weren’t the fact of a bombing, an epidemic or a tsunami; they were the result of the abrupt ending of industrial production and the transition from industrial capitalism towards its post-industrial version.

Spaces of industrial production were dismissed. Prior to its collapse, the mass scale industrial power of Detroit had given birth to an important social phenomenon in the history of the United States: for decades, it attracted a growing part of the Afro-American community (particularly those fleeing the brutality of racial segregation in the South), providing Black Americans wages, mortgages, privately owned individual houses, cars and access to the all the middle-class standards of living in general. The development of Detroit is genuinely historically tied up with the access for Black Americans to the benefits of capitalistic economy and the development of a Black American middle class.

And so, when the industry was taken away from Detroit to be relocated, it left out of economic resources a large community of middle-class Black Americans. In the mean time, this community had nevertheless gained the social, cultural and technological capital to invent new forms of cultural productions – all means of cultural representation – to contribute in telling the story of racial minorities from the perspective of class struggle in the US.

Detroit techno thus, tells a story of economic dispossession, urban decay, racialised class war and technology. It is very much imprinted with Afrofuturism, a form of magic realism that intends to fictionally and artistically rewrite the history of the Black American community. In doing so, it also revisits the relationship between humankind and machines, suggesting that humans and robots are both the victims of late capitalism and should emancipate together (rather than presenting machines as a cause of oppression).

Techno pioneer Derrick May, for example, is an advocate of what he calls “techno spirituality”, a form of elevated consciousness that we develop in collaboration with machines, about which he says: “techno dance music defeats what Adorno saw as the alienating effect of mechanization on the modern consciousness”. Similarly, Juan Atkins likes to cite Toffler’s phrase “techno rebels” as a source of inspiration for the type of musical creativity that techno has emerged from.

In order to move towards an architectural thinking of techno music, it is worth mentioning that the techno scene developed after, along and often in rivalry with the Chicago house music scene. Even if house and techno producers knew and inspired each other, the subcultural divergence is strong. When house can be considered as the successor of funk (if not a sampled version of funk), it carries on the hedonistic tradition of clubbing. House in its early form is also very strongly engrained in the queer scene. House is joyful, carnivalesque, it likes crazy costumes and make up, it is flamboyant and talks about sex,pleasure and excess. House likes to parody of the conditions of living under capitalism in general and the music industry in particular. Detroit techno in contrast is sometimes described as “intelligent body music”.

It is mostly straight though its producers (and consumers) like to demonstrate cyborg and machine-like asexualism. It reflects on the working conditions in late capitalism and the dematerialisation of culture. In other words, it addresses the politics and poetics of technology in a capitalistic economy which has abandoned the City, its dwellers and its machines.

Until techno music emerged in the dance music landscape, clubs were designated spaces designed to be clubs, because clubs are the product of a long history of regulating leisure. Techno is the first form of music that appropriated disused spaces of the city to make them clubs. It’s quite brutally obvious in Detroit and did transpose very well to post-wall Berlin, amongst other places across pot-industrial Europe. In terms of research, this allows us to circumscribe the kind of spaces we investigate around venues that became famous for club culture when they had been designed for it in the first place.

Interestingly, most of these spaces have been shot however famous they had become. Or even knocked down. Once closed, most didn’t live a trace in the urban landscape. Nevertheless, these clubs have a strong presence on the map of underground culture of the last 30 years.

Only few people remember any of their spatial features. This clearly makes the work of theorising their architecture much harder, unless we think about the architecture as a context of producing new forms of arts. The architecture of techno clubs must be read as a celebration of the social and cultural experimentations that emerged out of economic decay.