During the summer of 2024, an interesting experience was carried out in the Armenian Caucasus mountains. A group of people somewhere in a very rocky and wild environment gathered to construct an undefined and seemingly useless multi-species artefact.

During the summer of 2024, an interesting experience was carried out in the Armenian Caucasus mountains. A group of people somewhere in a very rocky and wild environment gathered to construct an undefined and seemingly useless multi-species artefact. They waked up at 5.30 am every morning, worked under an intense heating sun on an improvised construction site, prepared meals together three times a day, played football in the evening and sometimes danced at night. There were some wild dogs always around, horses as well, a couple of vultures close to where they were building, invisible and dangerous snakes, wonderful mantises. They seemed happy and tired. From far, the experience felt absurd and beautiful at the same time.

A brief introduction to their activities, from inside. A novel, first of all, a fictional story based on a historical event that happened in another part of the world: Switzerland. The novel is titled Derborence, written by Charles Ferdinand Ramuz in the early 20th century, and tells the story of a village community that suffered the consequences of a landslide. The novel is based on a historical event that happened in 1714 and caused the death of 15 people and 170 animals. Significantly, the death of animals was also recorded. This novel has given birth to an architectural trilogy initiated by BUREAU (Daniel Zamarbide, Carine Pimenta, Galliane Zamarbide). One first piece was constructed in a sculpture park in the Swiss mountains. The second in an art community in France. The third one, in the Caucasus Mountains in Armenia.

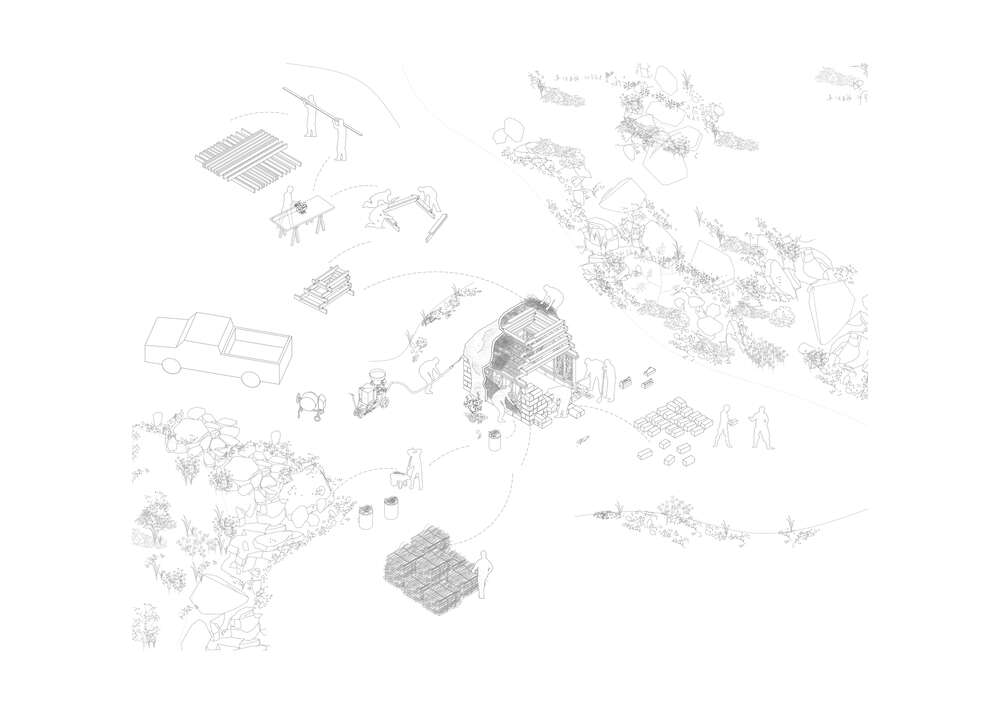

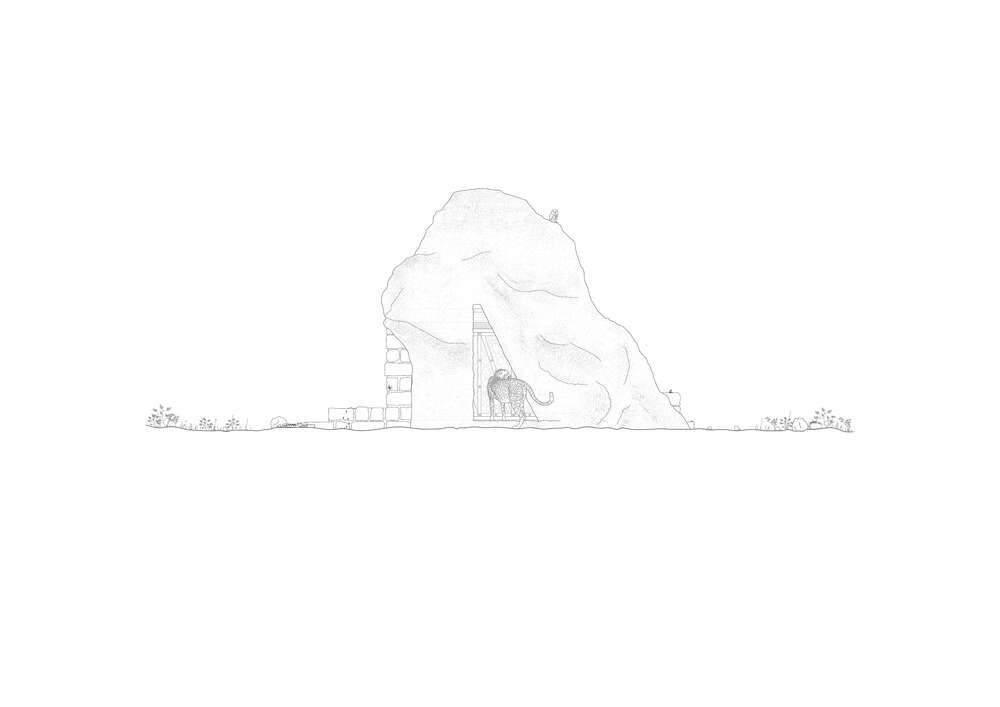

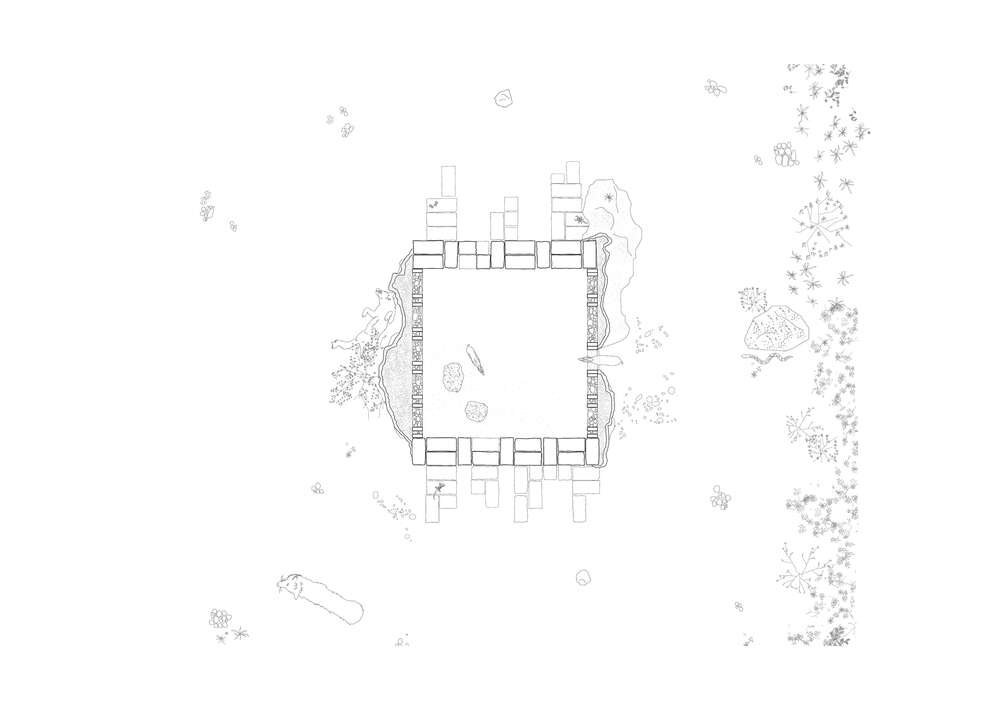

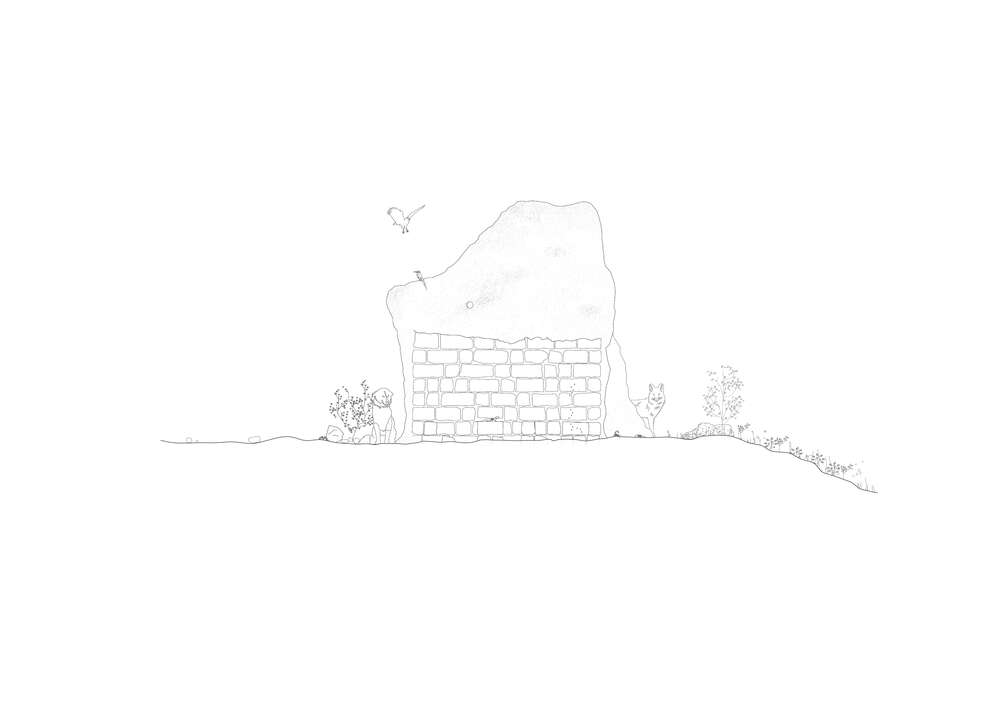

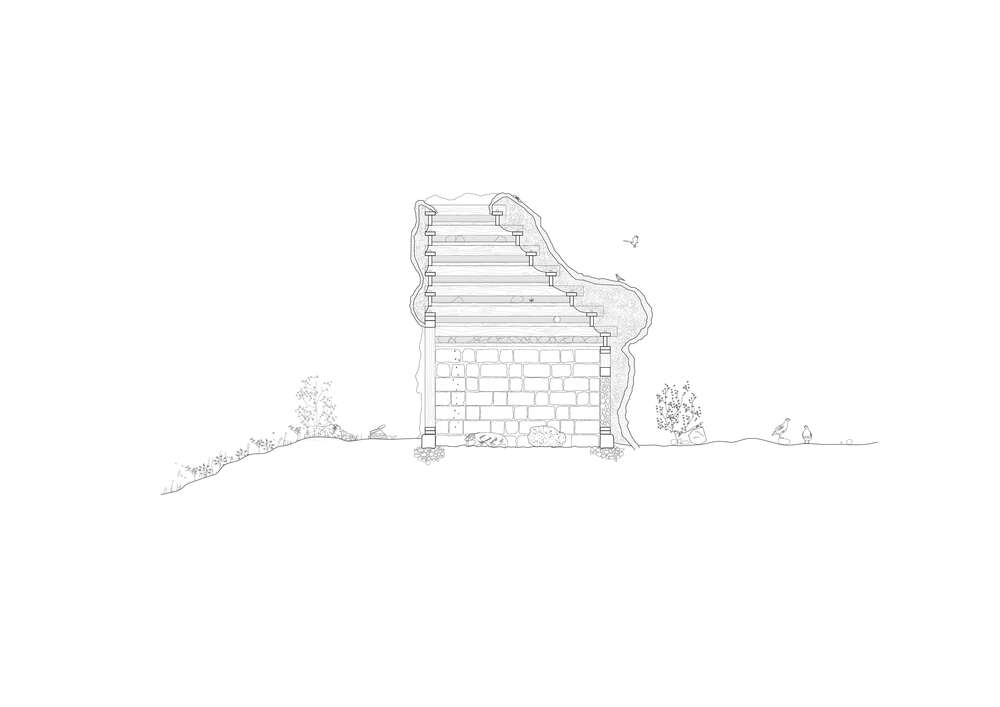

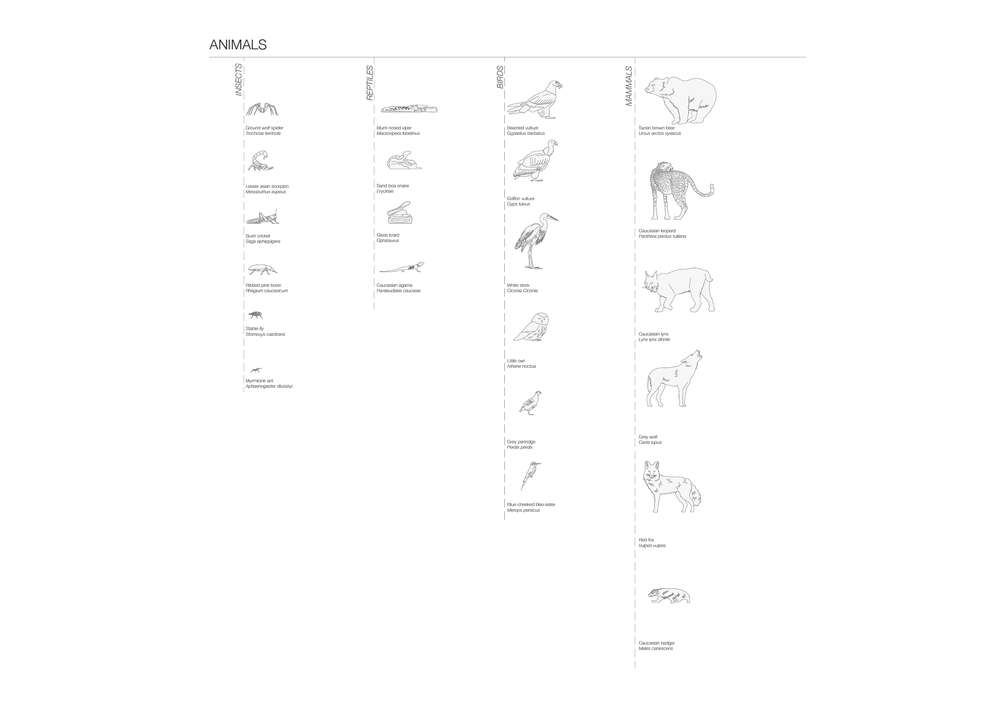

This last member of the trilogy is particular as it is not the result of a design by the Swiss-Portuguese architects but is a co-authored piece from BUREAU, NPATAK and 15 Armenian and international students, conceived and realized in a three weeks workshop in Yerevan, at the Library For Architecture for the first 5 days, and in the territory of the Caucasus Wildlife Refuge, a 30’000 hectares land of protected wildlife in South Caucasus. The process and result are part of a pedagogical approach that intends to dissolve thinking and making as part of a same undertaking. Architecture is mostly a theoretical practice, ironically quite detached from the physical part of construction. Since the renaissance, the architect has evolved away from the construction site, his.her main activity occurring today behind a computer. Historian Marvin Trachtenberg has marvelously described this decisive turning point in his book Building in Time. With a very different angle, sociologist Richard Sennet has made his own written trilogy - homo faber: The Craftsman, Together, Building and Dwelling - on this topic as well, developing a provocative idea that craft is really what matters when it comes to creative thinking-making. Pursuing the reasoning of Sennet, the foundational principle of the workshop was the following: People participate to the production of the world they live in, and they do so through conversing with the world, among themselves and with other living beings with who they share the environment. The workshop has been thus thought as a dialogical tool, a way to establish a dialogical exchange within a group of people who gather voluntarily together with the goal of designing and building something. The “something” is important but does not need to have a particular definition other than the fact of being open, porous and multi-species. A shelter, a mound, a reference point, a small environment that can be of some support for a diversity of fragments of lives that will occur in, or around it. The use of straw and rock provides shelter for those living creatures of various sizes.

The “building”, as a verb and as an act, is important as well. It says something about the temporary community that have had to organize as a group to think, eat, work, play, exchange together for three weeks in a quite isolated context. The consideration that a more than human population could somehow inhabit Séraphin of Urtsadzor has been very present in the development and making of the artefact. The function, or what in architectural culture is often referred as “program” is left open in this case. No specific usage but potentially a multiplicity of them. The object can be considered as multi-scalar as it welcomes and takes into account a diversity of inhabitants.

Text by Daniel Zamarbide