It is now more than 20 years since Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas published the definitive version of his theory of Bigness. This eulogy to Bigness has since become a classic work, allowing an understanding of both the end of the Modern era – from Mies van der Rohe to Le Corbusier – and the dawn of vast projects bearing the names of a few major figures, including Rem Koolhaas himself. “Beyond a critical mass,” Koolhaas explains, “each structure becomes a monument, or at least raises that expectation through its size alone.”

This “Bigness” – a popular trope among fin-de-siècle architects – is based on several core principles: the liberating power of elevators, the autonomy of different parts of a new building, a clear separation between indoors and outdoors and, most importantly of all, the fact that “Bigness is no longer part of any urban tissue”. It sticks two fingers up to context.

Over the space of 20 years, Bigness has become a mainstay of the landscape, from vast Olympic projects to Asian skyscrapers in cities such as Dubai and Shanghai. It is now up to the new generation of architects to criticise and rethink this trend, while proposing a new professional code and different ethics.

The recent financial and property crisis has led to the emergence of new social movements. In short, the game has changed. These movements initiate a discourse at a grassroots level, focusing on the needs of those for whom Bigness is simply out of reach. Across the globe, public squares play host to demonstrations that attract hundreds of thousands of citizens over several days. Irrespective of their temperament – indignant, angry or peaceful – these vast crowds create a new type of horizontal Bigness that is taking over large squares in some of the world’s major cities. In Paris, the Bastille was a monumental prison that symbolised the excesses of power. Once it was demolished, the site became a square synonymous with the Revolution. Thus, Istanbul’s Taksim Square, Cairo’s Tahir Square, Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, New York’s Zuccotti Park and Kiev’s Maidan describe a superlative, a levelled-out Bigness. All of these squares have one thing in common: they have become symbols of people power, where vast crowds gather temporarily for a few days. They are what Hakim Bey calls “TAZs” (Temporary Autonomous Zones). These TAZs poke fun at Big Business, forming assemblies, committees, security personnel and conscience groups to invent new ways of dismantling the structures and architectures of power.

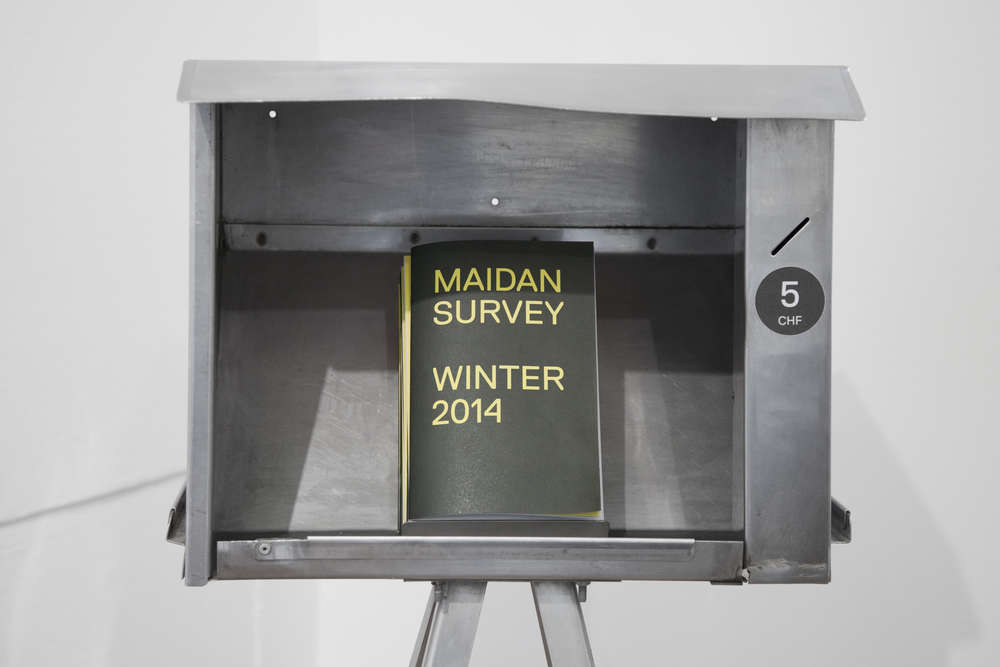

In Kiev, the square is known as Maidan (literally, “square”). Although it is now officially known as “Independence Square”, Ukrainians are aware that it has changed its name five times in the last century. In Maidan, where 15,000 people are camped, there is a need to organise the exorbitant disorder and to establish spaces, pathways and boundaries. In short, the protesters need to create their own autonomous zone architecture. In this case, however, the structure is no longer what the Modernists referred to as a “human settlement”. Instead it is a temporary installation, an emergency shelter with a unique function (kitchen, bathroom, library, hospital, place of worship) but also a shared function: a refuge against the bitter cold and snow of the Ukrainian winter. Occupied public squares have clearly defined boundaries: the limits of the autonomous zone mark the boundaries of the area controlled by the Power against which the protesters are demonstrating. In the streets that lead to these squares, the State installs security forces and hardware as a symbol of its power. These military and paramilitary personnel, protected in their trucks and barracks, defend their own zone, separated from the protesters by a no-man’s-land or a barricade.

The term “barricade” comes from the French word “barrique” (barrel), since these barricades were once made by rolling and stacking barrels to create a protective shield. These days, the barrels have been replaced by tyres, which are easy to roll, or by street furniture uprooted from areas where it hinders free movement through re-captured public spaces. In some cases, cars or even piles of television sets are used to create an obstacle. For centuries, barricades have come to symbolise a desire to regain lost freedom. They are a symbol of defiance against Bigness, against grandiloquence – a rallying cry for the power of what we might call “Smallness”. These barricades, bearing flags or draped with banners, mark the boundary of the autonomous zone. In Kiev, after months of resistance, another object has come to symbolise the resistance movement at the Maidan: the Roman shield or scutum. Initially used sparingly as a symbol of war, it has since been deployed on a massive scale. Unlike the shields used by the Teutonic Knights or Samurais, the scutum was a piece of curved, stretched hide designed to protect the full length of the legionnaire’s body. As such, a standard size was adopted: 130 x 67 cm. It is described at length in accounts of battles by Dio Cassius, but the most impressive account is that provided by Plutarch in his Lives of Illustrious Men, in a description of a battle between the Romans and the Barbarians:

In this case, the occupation of public space is not an urban theory concept. Instead it is a reality playing out on a resolutely human scale. It is an inverted form of Bigness, suited to the professional approach of the new generation of architects. These new architects are rolling their sleeves up and getting really stuck in. Give them a shield, a shelter or a barricade and they will create a small project out of it, the manifesto for how architecture will be in years to come.