One of the many misconceptions that has preoccupied the world of architecture in recent decades is that architecture’s noble existence occurs only in the built world.

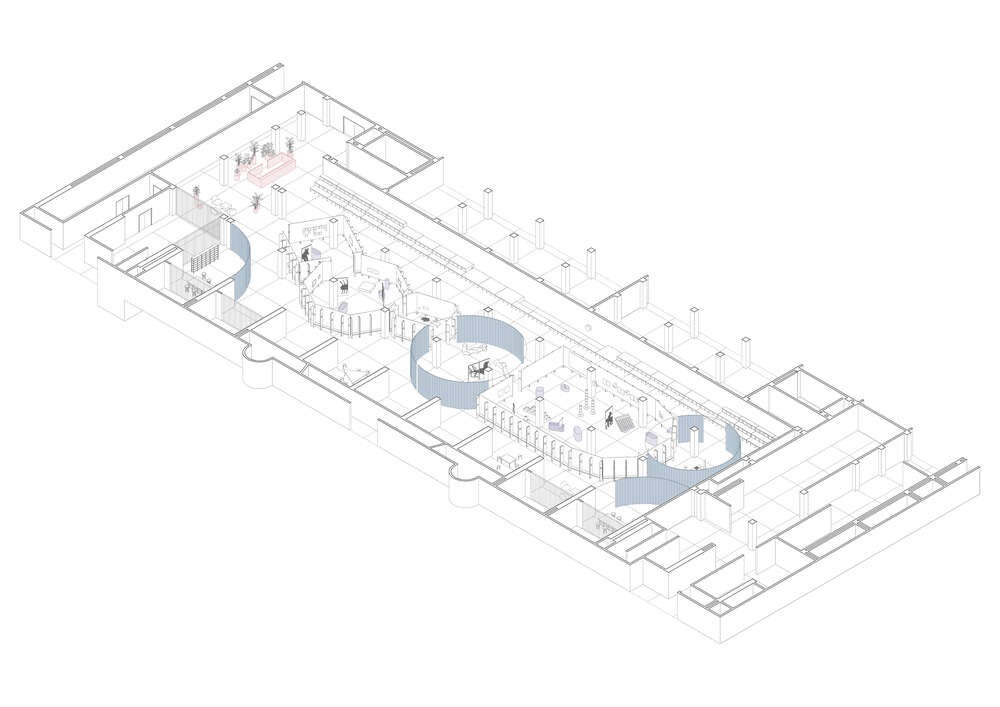

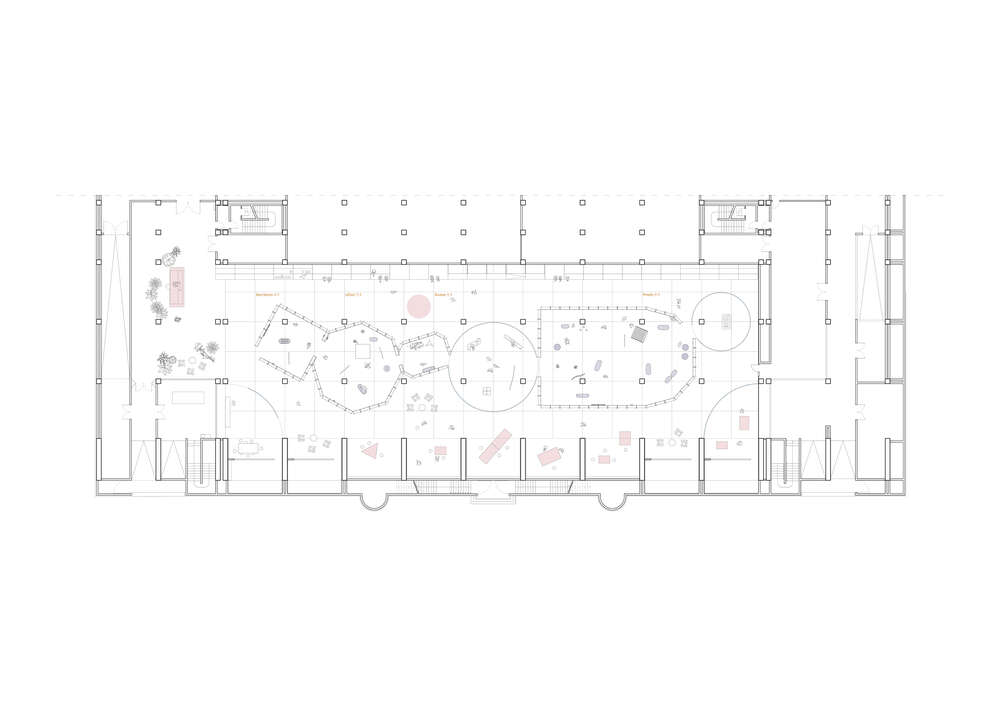

Buildings, in this narrative, are what constitute the real heart and body of the field. Everything else is anecdotal, peripheral, decorative, some would say with a touch of condemnation. If Carlo Scarpa’s work is remembered, it is not for what he did for most of his life and what he was truly dedicated to: Exhibition design, as Philippe Duboy has shown in his book “Carlo Scarpa, L’Art d’Exposer” (Les Presses du Réel). Making exhibitions was a political commitment in a particularly complex cultural moment in Italy, as was making wallpaper for William Morris in Victorian England. Others, like Lilly Reich, have literally disappeared from most architectural books, hidden behind a “master”. Exhibitions are public spaces. Everyone is allowed in to experience, discuss, learn or be informed about certain topics. If museums are the institutional containers of these public moments, exhibitions are the operational, public “rendez-vous” where the content is displayed and shared and where people hang out, come and go to be stimulated. There is no absolute truth in the way exhibition spaces have evolved, from classical museums with walls of colorful tapestries to today’s conventional white cube. They are all part of a history that can revitalize today’s rather standardized exhibition spaces. Within the diversity of possibilities, within the vast number of great exhibition spaces, some of them have come to Garagem Sul. They have landed in Lisbon to celebrate a contemporary, serious but relaxed way of looking at what is supposed to be a cultural institution. How should an institution be defined? Does it need a clear definition? Here is a small gathering of friends of space, some large and imposing, some modest and intimate. They have come to the Garagem party: Serralves from Porto, John Soane from London, El Prado from Madrid, the Uffizi from Florence. Fragments of multiple histories lived by millions. Displaced and re-enacted, they become less institutional, perhaps a little less stiff. To prove their informality, they show their organs. Backstage and frontstage are part of a nondichotomic ensemble. The technical and the representational are also merged in a single attitude to focus on the process of making, as in Harald Szeemann’s 1969 exhibition in Bern, “When Attitude Becomes Form”. And to a great percentage, the whole construction has used passed exhibition materials, re-enacting cultural moments and reclaiming existing elements from the space’s history.

And to a great percentage, the whole construction has used passed exhibition materials, re-enacting cultural moments and reclaiming existing elements from the space’s history. But before the party, and to give all these friends a proper welcome, the place was tidied up. Cleared of a number of elements that had appeared throughout the history of the architecture center. Natural light was there, but covered, inaccessible, hidden. And the original materials and configurations had suffered the normal layering of time. The exhibition that inaugurates this space is far from neutral: Interspecies. One that opens the world of architecture to necessary more-than-human approaches and attitudes. If many actresses and actors have been invisible in architectural history, other-than-humans were practically inexistent. The garage will then be ready to welcome wonderers of all kinds, to walk with history and the infinite stories that make it up. Daniel Zamarbide Lisbon Spring 2025