Counterculture seems to be a vanishing concept. One that used to be omnipresent 30 years ago and produced a considerable number of experimentations of all kinds (social, political, cultural) but that seems to have just left an aesthetic trace with a touch of nostalgia. Has this concept of counterculture been able to resist to the enormous machine of capitalist production? If art plays a role in defining “other” places, is there a possible space where art can develop with a relative amount of freedom avoiding market-oriented criteria?

Monday June 15th, Basel, I try to find my way in Art Unlimited, the “curated” part of Art Basel. Impossible to see the works, they are barely visible among the incredible crowd strolling around the Hall. Monday is the collector’s preview. Collectors hurry to get the best pieces. Guided by professional art counsellors they run around to obtain the most interesting investments. This event is followed by thrilling night parties. Celebrities show up and integrate the show, making of Art Basel an exclusive “destination” for a very specific public. Nothing to criticize about this, it is today’s art world, or at least an important side of it, everyone knows it, and most actors of this milieu play the game. Samuel Schelleneberg, art journalist at Geneva’s independent newspaper Le Courrier, has thoroughly described how purchasing art has become an attractive activity for many investors, and that this purchase comes with the added value of these very exciting moments of glamour, where collectors mix with extravagant and particular figures of the world of art, for a controlled yet slight decadent feeling, trespassing the limitations of everyday life.

But art exists in other forms as well. Although it is probably wrong to only look at them as a filial continuity of past countercultures, it is crucial to acknowledge their existence and their presence in the public realm. These forms have the power to provoke a larger debate about culture in general and its activation through art. BIG, the Biennale of Independent Spaces for Art in Geneva represents a remarkable initiative to bring out art to the city, literally opening its doors to everyone. Contrary to the settlements of the 70’s (Drop City, etc.) considered at times as too insular, BIG concentrates a wide variety of players that speak out for many reasons and purposes. Within the BIG manifestation, Art is many things, from independent book editors, experimental music clubs to theatre venues. And it’s absolutely public, held in a large open space in the centre of Geneva. In that sense, one could call it a popular or even populist event if we understand this term as defined by Ernesto Laclau in his text “On Populist Reason”. BIG is a necessary cultural form, making the manifestation a new necessity for the urban life of Geneva.

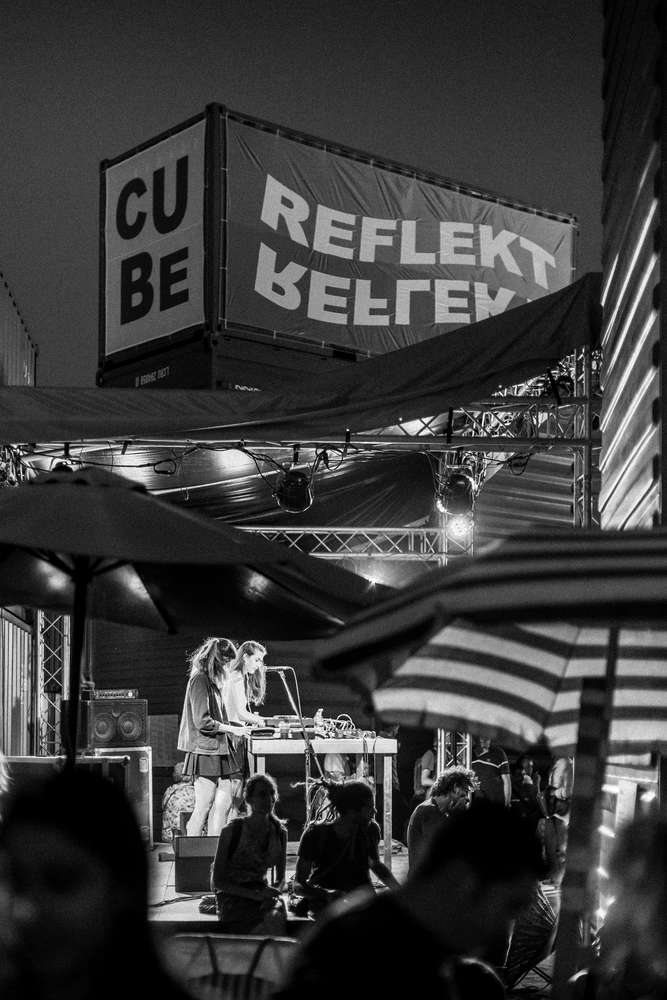

Friday June the 26th, I walk into Steelhenge, the name given to the settlement of BIG, echoing the mysterious and magical English Stonehenge. The memory of this mysterious and ancestral proto-installation is somehow present, even though the funeral ritual of the monument has disappeared to leave the space to the celebration side of the settlement. Dimensions of the original monument are kept, orientation too, the stones have been replaced by 48 blue steel volumes. No press preview here. Journalists, politicians, artists, passersby, art-public, can enter the space indifferently and constitute a heterogeneous crowd. It is very hot, provoking a general feeling of “elsewhere”, also helped by the aesthetic contrast of the blue maritime containers with the red soil of the public open space.

BIG is big, monumental in its ambition and form. It is an informal monument made out of people assembling for an unconditional engagement in culture and art. The people engaging in BIG present a real “lifestyle”, one that does not identify itself through branding, selling and buying but provides or even offers art to everybody, no status involved.